(I have a rough idea of the answer, but a little girl asked me this once, as is, and I want your take)

“How do tiny ants walk upside down? Do they wear glue on their feet?”

(I have a rough idea of the answer, but a little girl asked me this once, as is, and I want your take)

“How do tiny ants walk upside down? Do they wear glue on their feet?”

What’s your favorite ant?

Ha ha! You have inadvertently asked me two questions that are closely related!

@coralinecastell and @xist your answers are closely related.

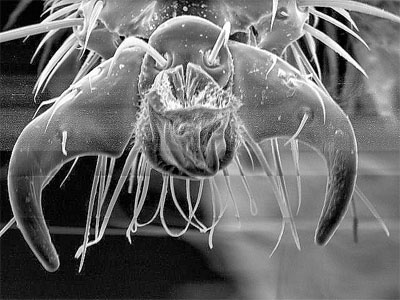

The bottom of an ant’s foot (and in fact most insect feet) looks like this:

Using this combination of hairs & the claws they can cling to irregularities in surfaces. Most methods of preventing ants from getting on surfaces covers those irregularities. But this means they put all their body weight on the little claws. So @xist as ants get bigger more and more weight has to go onto those claws. So as they get bigger, they take more and more weight, and eventually they will break. Don’t fear big insects. And most insects don’t have glue on the bottoms of their feet, they instead have lots and lots of hairs.

@Pylinaer that is a really hard question, but honestly I couldn’t tell you… I love a lot of ants… it is hard to pick just one.

how do I delete someone else’s picture?

thanks for answering!

I put a spoiler box for you

I have always wondered how the chemical communication thing worked, eg how they produce/detect the chemical and how they distinguish their own chemical from another colonies in terms of trails to food. Also how rudimentary/complex is this form of communication?

Another question that, like the complexity of the nest, is really dependent on the ant species in question.

This question required the use of that incredibly useful tome: The Ants. The Ants - Wikipedia

If you intend to know things about ants, this is one of four books that you really must own (the other three being 2 other books by Hölldobler and Wilson, namely The superorganism and possibly Journey to the Ants (a much reduced version of The Ants), the third is a guide to the genera/species of ants found in your area of the world, though ideally this may require two or even three books to accomplish as regionally comprehensive ant guides are notoriously sparse).

Now to the answer:

Chemical communication is accomplished by the use of numerous chemicals. The ants has an entire chapter devoted to this topic, and I will attempt to summarize here. I will admit that I doubt my ability to accurately summarize 71 pages of dense literature into a single post, but I will try.

Some chemicals are simply on the body, and help an ant recognize which colony they are from. It is these specific chemical signals related to physical ant bodies that help them determine if they are from the same colony. Ants also produce chemicals when they die that workers use to recognize that something needs to be removed from the colony.

The chemicals I imagine you are most interested in are those used to lay down trails informing ants about where food can be found, when to attack intruders etc. These are called semiochemicals and pheromones. In some ants this chemical signaling is incredibly complex where the ants have an entire suite of special glands and secretions they can leave to create a wide variety of messages (glands of interest are the poision gland, Dufour’s gland, Pygidial gland, Sternal and Rectal glands plus mandibular glands and Cephalic glands, but not every ant has all of these, or even uses their excretions for communication. it gets really complex really fast). Other ants just have one or two glands, or don’t really leave chemical messages at all. Some ants just have more research done on them, carpenter ants and fire ants have a great deal of the messages ‘interpreted’ while some other species are basically assumed from our research on these more economically impactful groups. A tiny amount of a single pheromone has huge behavioral consequences for a colony and the specific ‘blend’ of pheromones elicits a specific response.

If you can find pictures of them Table 7-4 (a 2 page table of alarm pheromone compounds in different species) and 7-5 (a 2 page table of trail pheromone compounds in different species by genera) and 7-6 (a 1 page table of trail pheromones by type) will likely give you a good idea of the complexity involved here. Actually there are tons and tons of pictures in this chapter of The Ants, many of which are quite helpful to understanding what a specific ant uses to communicate, and how the brain/sensory system picks it up. @PeteMcc here is a link you may find useful, or just way to much info: http://www.antwiki.org/wiki/The_Ants_Chapter_7

As to the ability to discern signals ‘from the colony’ vs from others, think of these signals like a telegram, unless you recognize the number you can’t really tell the difference between senders. Often scientists can create signals in the lab by simply placing these chemicals where they want ants to go (there are some pretty interesting experiments that show that if you coat a living ant in those corpse recognizing chemicals, then other workers carry that ant off to the graveyard and will keep bringing them back when they leave). So if an ant encounters another colonies foraging trails out in the wild they might follow them like a normal foraging trail until they encounter another ant (assuming they don’t smell the new colony).

And I haven’t seen Antz, so I couldn’t tell you.

A special thank you to @PeteMcc because their question necessitated my linking to the antwiki summary of The Ants chapters, when I realized that some useful information might be found there to answer a few prior questions as well. (Think of this as optional reading if my answers prompt more questions). Although I linked to Chapter 7 in the post above, from there you can see any chapter in the ants. With a description of what is in it. I strongly advise skimming as some sections even have pictures!

Thanks for the answer. Very informative, I will have a look at the wiki link when i have some more time.

As someone currently living down under, are there anything like the honeypot ants you find here, and what makes their abdomens(?) be able to stretch like that? It seems so amazing that they can carry around all that “honey” and regurgitate it back out to the other ants in the colony on demand.

This goes for most insects afaik, but why are ants always going as high as they can? When I have one check my hand out they always run up  (I can understand that for insects with wings, not so much regular ant workers)

(I can understand that for insects with wings, not so much regular ant workers)

Also how come some are extremely hectic and prone to running off edges and falling? I understand there are different kinds of workers, but this ultra hectic behaviour doesn’t seem useful at all haha

Honeypot ants are found in North America, Mexico as well as Australia. What makes their abdomens stretch has to do with the structure of the insect abdomen.

@anon63424221 , I will have to do some research into the erratic behavior, but I think the climbing can probably be explained with some reading on ant exploratory behavior (they tend to look for boundaries in enclosed spaces). But I will double check and write a full report in a bit.

Hmm… I’m really liking these ants. Not sure why

Or should my appropriate response be that I would avenge them?

Edit: Thanks for the info! I’ve always thought ants were pretty cool

Sony has enough money to buy take two?

That’s so cool! Thanks!

how long before those SA jungle militant killer ants make their march to the rest of the globe and swarm humankind (becoming the new dominant species) -and could they adapt/survive the cooler northern climate if they “decided” to invade ?

(ie. AM I SAFE IN SCANDINAVIA FROM THESE VERY REAL but tiny MONSTERS?)

To first try and address @anon63424221 's question: some ants simply move way faster than other ants. The Formica ants especially move quite quickly. And as I mentioned in Coralinecastell’s question above ants can cling to surfaces using those claws and hairs at the ends of their legs. The faster an ant moves the more likely they are to ‘misstep’ (the same is true of people, which is why you shouldn’t run on ice or uneven surfaces). So depending on the species ants may not be ‘jumping off edges’ as much as they are falling off by accident. Larger ants are even more likely to fall than small ones, but some small ones can also fall.

The hectic behavior in question may just be because you are a big scary shadow, that disturbs the ants and causes them to try and run away (or seek shelter). Them falling off the ledge may have less to do with the speed of their motion and more to do with them trying to get far away from you.

To return to the question of why climb up? Ants are big on determining the boundaries of a space (especially trying to determine the extent of their own territory) rather than what a space contains. This helps a colony take up the largest territory possible, at least theoretically. Of course, taller objects like blades of grass or other plants tend to have insects on them, so a foraging ant looking for some food would be wise to climb up those structures looking for insects.

@yoel666 I don’t consider myself educated on the topic, but I doubt Sony has the liquid assets on hand to simply buy take two, especially given the fact that GTA 5 is the most profitable entertainment product ever. However, if they were willing to mobilize some of their physical

investments or other forms of capital I don’t doubt that Sony could make a pretty good offer.

To answer this question with ants, I am going to take a page out of ‘Bunnies & Burrows’, and say that to the ant (which can count the number of steps between them and their nest in order to find their way back home When Ants Go Marching, They Count Their Steps | Live Science Oh,@yitzilitt that’s another one… the stilt experiment was still big when I was entering grad school) both Take two and sony’s respective cashflows would be huge and immense distances they wouldn’t ever consider walking, the influx of respective cash would be on par with the caloric intake of the biggest ant colonies on the planet. I doubt ants would consider it “normal” for those two companies to try and merge into one. In normal ant colonies the only reason for those sorts of interactions is that one of the companies would be feeling incredible stress from another direction and had no other choice but to try and muscle in on the territory of the other colony. Ant colonies create little zones of ‘no mans land’ between them and typically have very little actual combat between colonies of the same species.

@Gnuffi I am unsure what ants you are referring to, the bullet ant perhaps? Or maybe some internet invented army ant? Ants have already shown themselves to be quite adaptable to cooler climates, and with global climate change they are likely to be able to enter further north. The biggest issue facing the northern expanse of SA jungle ants would be the loss in biodiversity that the are so dependent on. The main reason so many tropical ants are so big and so ‘exotic’ is the huge food availability the colony can access year round. So as the ants go north they are likely to grow smaller, as they have less food available to them. Also, if they were to expand up into NA they might face some issues from the already invasive species (especially the 2-3 argentine ant colonies that make up all of California).

Antwiki identifies 75 ant species known to Sweden, so Scandinavia certainly has some potential for new ant species to join the mix. http://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Sweden

In all honesty, you have more to fear from the smaller invasive ants that plague many port cities moving in to city spaces.

remember seeing something about them marching/“moving colony” quite far too, and sorta “laying areas bare” in their wake ![]()

-sounds kinda like scary little critters ![]()

If you want to learn more about them… Gotwald is your man. http://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Gotwald,_William_H.,_Jr. (Link is now broken, will find new one at some point).

He wrote the book on army ants, quite a good read in my opinion.

As to if they could manage in particularly cold climates… It doesn’t seem likely, the furthest north they go is probably South of Central USA. They tend to be found in deserts/jungles. A shame if you ask me.

Fun fact you might not know: army ants actually support entire subcommunities of myrmecophilic insects and arthropods (like there are a tremendous number of organisms that are ‘hangers on’ around an army ant colony, and they are not found anywhere else. Like silverfish, beetles and others.)

Trigger warning for @coralinecastell more ant feet (sort of):

But army ants even have birds that follow in their wake and catch insects that fly away from the advancing armies. Following the army ant-following birds | OUPblog