Another question that, like the complexity of the nest, is really dependent on the ant species in question.

This question required the use of that incredibly useful tome: The Ants. The Ants - Wikipedia

If you intend to know things about ants, this is one of four books that you really must own (the other three being 2 other books by Hölldobler and Wilson, namely The superorganism and possibly Journey to the Ants (a much reduced version of The Ants), the third is a guide to the genera/species of ants found in your area of the world, though ideally this may require two or even three books to accomplish as regionally comprehensive ant guides are notoriously sparse).

Now to the answer:

Chemical communication is accomplished by the use of numerous chemicals. The ants has an entire chapter devoted to this topic, and I will attempt to summarize here. I will admit that I doubt my ability to accurately summarize 71 pages of dense literature into a single post, but I will try.

Some chemicals are simply on the body, and help an ant recognize which colony they are from. It is these specific chemical signals related to physical ant bodies that help them determine if they are from the same colony. Ants also produce chemicals when they die that workers use to recognize that something needs to be removed from the colony.

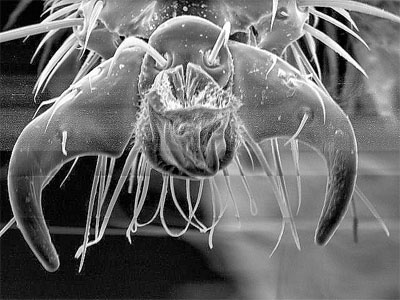

The chemicals I imagine you are most interested in are those used to lay down trails informing ants about where food can be found, when to attack intruders etc. These are called semiochemicals and pheromones. In some ants this chemical signaling is incredibly complex where the ants have an entire suite of special glands and secretions they can leave to create a wide variety of messages (glands of interest are the poision gland, Dufour’s gland, Pygidial gland, Sternal and Rectal glands plus mandibular glands and Cephalic glands, but not every ant has all of these, or even uses their excretions for communication. it gets really complex really fast). Other ants just have one or two glands, or don’t really leave chemical messages at all. Some ants just have more research done on them, carpenter ants and fire ants have a great deal of the messages ‘interpreted’ while some other species are basically assumed from our research on these more economically impactful groups. A tiny amount of a single pheromone has huge behavioral consequences for a colony and the specific ‘blend’ of pheromones elicits a specific response.

If you can find pictures of them Table 7-4 (a 2 page table of alarm pheromone compounds in different species) and 7-5 (a 2 page table of trail pheromone compounds in different species by genera) and 7-6 (a 1 page table of trail pheromones by type) will likely give you a good idea of the complexity involved here. Actually there are tons and tons of pictures in this chapter of The Ants, many of which are quite helpful to understanding what a specific ant uses to communicate, and how the brain/sensory system picks it up. @PeteMcc here is a link you may find useful, or just way to much info: http://www.antwiki.org/wiki/The_Ants_Chapter_7

As to the ability to discern signals ‘from the colony’ vs from others, think of these signals like a telegram, unless you recognize the number you can’t really tell the difference between senders. Often scientists can create signals in the lab by simply placing these chemicals where they want ants to go (there are some pretty interesting experiments that show that if you coat a living ant in those corpse recognizing chemicals, then other workers carry that ant off to the graveyard and will keep bringing them back when they leave). So if an ant encounters another colonies foraging trails out in the wild they might follow them like a normal foraging trail until they encounter another ant (assuming they don’t smell the new colony).

And I haven’t seen Antz, so I couldn’t tell you.